Brain research is one of those many scientific fields that I’ll never know much about, but I find it important to get even a limited understanding of the direction of recent findings. It helps me to know, for example, that emotions are generated unconsciously through multiple brain systems before anything gets to awareness. As I wrote in the last post, that opens a different outlook on why it’s so hard to get rid of depression.

Hard, but not impossible. And that’s the other side of the story I’ve been looking into with the aid of books like Joseph LeDoux’s The Emotional Brain and Daniel Siegel’s The Developing Mind

. Therapy of many types can work, and these authors offer a lot of ideas about what makes that possible. To do so, however, they have to get into big questions about consciousness, memory or personality that are not well understood. Fortunately, these writers are quite clear about where research ends and their own informed speculation begins.

Several of their ideas fit well with my experience.

Getting Stuck in Memory

According to LeDoux and Siegel, the brain can learn to reduce the impact of powerful emotional signals. To begin with, one of the results of this complicated system itself is to regulate emotion by sorting it out and giving meaning to all those highly charged signals that force the mind to pay attention. Without the ability to recognize feelings, the brain would be at the mercy of every strong jolt of energy surging through it. There would be no control at all.

Instead, each surge is evaluated as it moves through different parts of the brain and winds up rushing into what Siegel and LeDoux call a working space of memory. There the signals are matched to long-term memories associated with similar situations. Those are the memories that had the strongest emotional charge when the events they recall took place. That charge is what focused our full attention in the first place and now makes keeps them close to awareness and easy to summon up.

Those memory links bring to consciousness a feeling that’s familiar from earlier experience. I’m putting all this very roughly, but at the end of the line, I feel depressed or thrilled or angry. That’s what I’m aware of. All the rest, leading up to that moment, happens so fast, it seems I’m directly and instantly reacting to whatever is going on.

As Siegel elaborates, most people retain a flexibility in this process and respond appropriately to what they’re witnessing in the present. They have the feeling, it ends, and they move on. But many of us have a tendency of mind to interpret events consistently in one way. An explanation could be that certain memories – especially of experiences repeated over long periods of time, like psychological abuse – override everything else.

The mind gets stuck in linking present moments to those most painful memories and reacts with feelings more appropriate to the old experience rather than the new one. As LeDoux points out, weakening the power of those memories may be one of the benefits of psychotherapy.

Learning from Different Forms of Therapy

That insight and several others suggested by research help me understand why I’ve had to combine several forms of therapy and healing. Three, in particular, have made the greatest difference in enabling me to get out of this memory rut and also break the mental habit of seeing most experience in negative terms. Those three are “talk” therapy based on psychoanalytic methods, meditation and mindfulness, and cognitive therapy.

-

Psychoanalytic Therapy: – When I started looking for help, there was one option – psychiatry. Over the years I worked with several who were trained in Freudian psychoanalytic techniques. The most important part of this for me was recognizing and bringing to the surface traumatic events of family history. Those were the powerful long-term memories that LeDoux and Siegel describe. Just as they say, the emotional force of those memories distorted the way I interpreted experience and locked me into responses that related to the past, not to the people and events of the moment.

Those psychiatrists were not treating depression directly, though, and therapy sessions didn’t diminish its power over me. Their importance was in making me aware of the deep emotional responses that I’d buried. Gaining that awareness was the first big breakthrough that made later progress possible. At least I had a good idea of what was happening in the memory-linking process and had an invaluable set of tools for making it more adaptable to reality.

-

Meditation and Mindfulness: This approach has been a powerful method for focusing my attention on the present, further helping me break the power of the most negative past experiences. But even more important, the practice of meditation and mindfulness has enabled me to detach just enough from the flow of inner experience and depressive tendencies to see them as separate from a more comprehensive sense of myself. I could begin to see that there was more to me than the portrait painted by depression.

In terms of the recent brain research, I seem to be getting into that final stage where the conscious part of the brain interprets the signals it’s receiving as particular feelings – sadness, excitement, fear. Mediation focuses on that process, and I get a sense that the depressive feelings I experience may not be so inevitable. I could never sustain this sort of mindfulness to get to a level in which depression might disappear. But I could get to the point, for brief periods, where I felt I was almost watching my mind interpreting everything negatively.

-

Cognitive therapy: As I can understand it, cognitive therapy helps recondition the tendency to see experiences through a depression lens. This takes what I can grasp in meditation only briefly into the details of life situations. The most important part of the cognitive approach for me is learning how to interpret experience in realistic terms. This seems to be part of what Siegel refers to as flexibility of emotional responses. By considering the multiple meanings that any event could have, I’ve learned to break the habit of assuming the worst about each situation. Look at the facts first, rather than the assumptions.

That’s a simple yet powerful tool for separating the feelings of depression from everyday experience. It took me a long time to internalize this way of thinking, but now it’s hard to imagine how I could have imposed my feelings and assumptions on so much over so many years. That old ingrained habit was one of the key supports for depression, and over time I learned how to change it.

I believe that these and other forms of healing I’ve used over many years finally influenced the unconscious processes that LeDoux and Siegel describe. Perhaps that’s why I could never figure out exactly what had happened or when to make me aware that I was no longer controlled by depression. I’ve described recovery in terms of a deep internal shift, something I felt and experienced but couldn’t name. The research gives me a new way of thinking about that change.

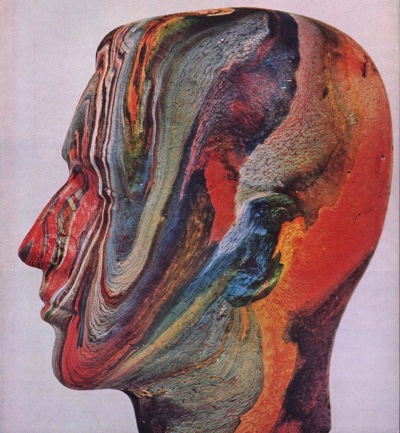

Some Rights Reserved by A Journey Round My Skull at Flickr

This is a beautiful and articulate presentation of what has obviously been a profound journey for you. Reading this helped me step back take my own gradual healing journey into perspective as well.

It’s a powerful notion that we can change our deep seated emotional patterns. Whether they are rooted in the brain or the body/brain complex, either way what’s important is that we ‘can’ change them. This is extremely good news for individuals suffering from various emotional and/or psychological afflictions, and for humanity as a whole.

Thank you for this uplifting read. It helped me wake up.

Thanks, Craig –

My ability to deal with depression has depended on finding ways of stepping back and separating my sense of self from this condition. I’m very glad to learn about your site and its approach based in Buddhism and mindfulness – meditation and mindfulness have been important dimensions of my own recovery. I also spent many years as a mediator at an institutional level and learned a lot from that experience. Since we seem to share several interests, I look forward to reading about your insights on anger.

Thanks for coming by –

John