Understanding depression and getting serious about recovery take a lot of searching. Reading is one of easiest tools to use, and the classic books in this highly personal list may help you get started. They have opened my mind to dimensions of healing I had never before paid much attention to.

In particular, the five books I describe in this post have sharpened my sense of what life could be like without depression. They have helped me think through what I’m aiming for while offering specific methods for getting there.

Here are the five:

-

On Becoming a Person by Carl Rogers.

This is a collection of essays by Carl Rogers, the originator of person or client-centered therapy. While depression comes up in many of his descriptions of therapy sessions, this isn’t a book about depression. It’s an exploration of what becoming fully human can mean and the life you can live once free of the distorted feeling and thinking so typical of the illness.

While I find the essays throughout full of helpful insights, I especially value those in Part III (The Process of Becoming a Person) and Part IV (A Philosophy of Persons), along with the opening essay, This Is Me. These present Rogers’ fundamental ideas about the good life.

He sees it as a “flowing, changing process” in which a person is fully open to learning from experience, fully aware of feelings and able to express them. Living this way means being free of the defensiveness which narrows life by excluding anything that threatens a fixed view. A well-functioning person isn’t bound by rigid preconceptions of life but is responsive to people and circumstances on their own terms – the “ever-changing complexity” of living. Rogers put it this way in describing his own life:

To experience this [process] is both fascinating and a little frightening. I find I am at my best when I can let the flow of my experience carry me in a direction which appears to be forward, toward goals of which I am but dimly aware.

These insights, which are just a few among hundreds to be found in Rogers’ writing, may sound familiar because so many of them were later rediscovered and popularized. For example, I’m sure he was the first psychologist to use the phrase “living in the moment,” not as doctrine but as an idea that helped him understand what he was learning.

All the essays in this book were written between 1952 and 1961 and based on his work in the 1930’s and 40’s. He paid attention to his experience as a therapist and as a person rather than to any theory. That’s why his ideas have helped me understand what life without depression could be like.

-

I Don’t Want to Talk About It by Terrence Real.

Terrence Real’s work with couples and families led him to identify depression in men as a major source of conflict. His book is one of the few on this subject, and it’s full of powerful scenes from his practice. He believes that the anger, blaming and aggressive behavior of many men within their families derives from what he calls “covert depression.”

He traces this to the shaming and contempt boys often grow up with if they behave in ways that seem overly emotional to parents and peers. Although I think shaming has many other causes, Real emphasizes the pressure to fill the conventional masculine role as the most important one. That means showing external strength while holding back and never talking about feelings or inner pain.

Real points out that if a boy fails the test of manhood, he is branded as feminine, a sissy, a coward. But if he passes, he is encouraged to dream about his future in a grandiose way. The combination of shame and grandiose hopes, that are often disappointed, causes many men to conceal their inner selves behind work, drink or rage. This covert phase can lead to overt depression, which, in turn, is denied and hidden.

I think there’s a basic truth in this concept, and it has helped me understand the connection between my own rages and depression. The recognition for me came mostly through reading Real’s intense portraits of family confrontations and therapy. It was like looking in a mirror, and his final chapter about talking with his dying father was perhaps the most moving of all. You won’t find another book quite like this one.

-

Opening Up by James Pennebaker.

Pennebaker is the researcher who helped me understand the value of writing in recovery from depression. He found that people who had lived through traumatic events could be helped in unexpected ways if they could express their deepest feelings, either by talking or writing about them. They had far fewer health problems of all kinds following the trauma than those who did not open up about their feelings.

He probed further in his research and linked the effectiveness of opening up to the need people have to explain things and reassure themselves that the world is a stable place. Writing to confront unexpressed feeling helps do that by providing a sense of direction and meaning. There is an emotional completeness achieved by the ability to express and explain. When the feelings and experiences begin to make sense, you go from being overwhelmed and helpless to being mentally and emotionally active.

The words and sentences help to organize and simplify what you’ve been living through. When you have the ability to explain something verbally, you feel more confident that you really understand it. Pennebaker found that when trauma victims wrote about their experiences for several days in a row, the writing became more concise and organized, more focused on the event itself. Until they started writing about what they felt during the experience, they could not put the trauma into words at all.

He applied the same idea to depression after finding that writing about his own episodes had helped relieve the worst symptoms. After more research, he developed a valuable set of do’s and don’t’s for the effective use of writing as a form of therapy. You can find a detailed discussion of them in this earlier post.

-

Lincoln’s Melancholy by Joshua Wolf Shenk.

Lincoln managed his depression without medication or psychotherapy, and it’s the argument of Lincoln’s Melancholy that his response to the illness was a major influence in his life and career. He resisted the destructiveness of depression, which almost pushed him to suicide in his mid-twenties, with his focused mind and will. Those are two qualities that tend to vanish in the midst of severe depression, but he seems to have used whatever faculties that remained to great effectiveness.

Driving him to overcome depression was the great strength of his commitment to a purpose much higher than his own well-being. That was nothing less than trying to save the institutions of freedom in the republic. Once that purpose was clear, he could see his dark melancholic periods as times of testing, renewal, even spiritual growth.

This was so even though each breakthrough in advancing his and his country’s goal was followed by more depression, tragedy and personal suffering, concluding with his own assassination. Especially toward the end, he was able to achieve a serenity about his condition when he looked toward a rebirth of freedom in the United States following the Civil War.

However grim his life became, he never ceased to cultivate the self-discipline that was his basic tool in gaining stability. Many observers noticed his frequent withdrawal from others, often in the midst of a public gathering, to retire into a striking gloomy meditation. Yet these retreats, Shenk speculates, could have reflected not the domination of the man by his melancholy but rather the outward signs of his struggle to gain control over its effects.

-

Learned Optimism by Martin Seligman.

Learned Optimism is an extremely informative introduction to some of the research and theoretical thinking behind cognitive behavioral therapy and positive psychology. Seligman traces the experiments that led him to understand the powerful influence of expectation on the way we think and feel about experience. As he sees it, repeated painful experience, such as childhood abuse – events that we are helpless to change – can lead to the permanent expectation of helplessness in the face of difficulties and setbacks.

When helplessness is internalized or learned, it generates the symptoms of depression. These become a permanent part of living when intensified by a pessimistic style of thinking. There are three main types of distortion such thinking imposes on reality. You turn every problem or setback into proof of your failures and believe that you can never change. You come to expect that everything in your life will turn out badly, and you see yourself as the cause of all the bad things in your life.

In Seligman’s view, cognitive therapy relieves depression by changing the pessimistic style of thinking to a more optimistic one, that is, by learning optimism and unlearning pessimism. The therapy does this by helping you review the phrases and thoughts you use to explain bad events and then practice substituting more realistic explanations. That means looking at events from perspectives other than your own and considering alternative explanations. Gradually, the fixed expectations of failure, disappointment and helplessness give way to a much more balanced way of interpreting life.

While I have my reservations about cognitive therapy, it is the dominant form of psychotherapy for depression and many other disorders. Learned Optimism is the most engaging and helpful summary of the approach I’ve yet found.

Have any of these books been helpful in your work on recovery? Are there others we should add to the resource list?

I should explain that I haven’t included any of the excellent first-person stories about depression, but that’s only because there are so many that they need a separate review. They’ll be featured, along with many other resources, in future posts.

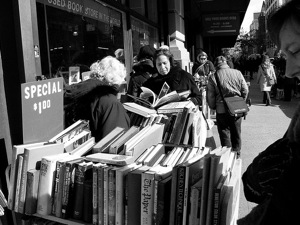

Image by ktylerconk at Flickr

I have read Terrence Real’s book and thought it was very insightful about depression in men. I think the title is very apropos! I think my husband found it helpful, but then he doesn’t want to talk about it!