This revised post from the early days of Storied Mind seems especially relevant to the work I’m doing with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Sometimes I’ve interpreted certain life and career choices of the past as avoiding depression. At other times, I’ve seen them as accepting the need to deal with it rather than play a new career role to cover it up. The different ways I look at the past in these two posts makes me realize that interpreting earlier life is far less important than staying alert to every present moment. You can learn many lessons from the past, but the only choices you have control over are the ones you’re making right now.

I was reading Joyce Carol Oates’ novel, Blonde, about the life of Marilyn Monroe, and was stopped by a line spoken by the character known as the “The Survivor.” He said that Norma Jean was a natural actor because she didn’t know who she was and so was driven to become her character completely. Acting meant reaching into the fictional being to become that person totally. She had to fill an emptiness where most people had a strong sense of self.

This idea suddenly helped me understand my own experience with acting as a depressed twenty-something. Then I started thinking about the many other types of work I’ve done and the role that each job required me to play.

I had turned to acting in the first place out of a core belief that I was wrong the way I was. I needed a self I would be proud to show the world. Stepping into a scripted role and winning the applause of a live audience made me feel that I had a reason to be alive. What drove me away from acting was an inner refusal to construct myself out of assumed identities and to depend on the highs offered by approving audiences – highs that could turn quickly to lows of rejection. Of course, I can see that in hindsight, but at the time I took the applause at face value, yearned to have it and fled in terror if I lost it. The approval meant I was worth something. The rejection meant I was nothing.

Audiences want a lot from an actor. They want to hear you speak the script as if the words were naturally yours and forced out of your own feelings and life. They want to see you walk that character’s walk with perfect balance. Each person in the darkened theater wants you to help them forget the clumsy machinery of a stage, painted sets, creaky seats, coughing neighbors, rattling thoughts.

Pull us out of ourselves, shut up our chatter, knock out our critical minds so we can be feeling what you’re going through in the workings of the play. Make us laugh, cry, forget ourselves for a time, and we’ll love you. But stumble around, speak a false or stilted word, hide that character from us, and you might as well turn on the lights because we’re leaving and won’t forget or forgive your failure to carry us away.

And there I was trying to do the same thing – lose who I was and live in a role for a few hours, to be rewarded, as I so deeply hoped, by the enthusiasm of an applauding crowd. I won some and I lost some, but I was desperately searching to be “real” in every role on every stage.

Eventually I gave up acting altogether, and for a long time I thought I had made the choice out of fear. I believed I had run from the need to get to the bottom of who I was. I saw myself in defeat, flight, cowardice. But that was the way my depressed mind characterized everything I did. It took years to see the more positive side of what I was doing.

For it was, in some ways, the choice of a stronger self than I imagined I was. That self was saying No to the desperate need to disappear into someone else, saying No to the yearning, literally, for the applause of a vast audience, saying No to the need to be known as that gifted actor who walked about most of the time inconspicuously, who didn’t need to live a full life off the stage because his true existence and value emerged only in the darkened space of a theater.

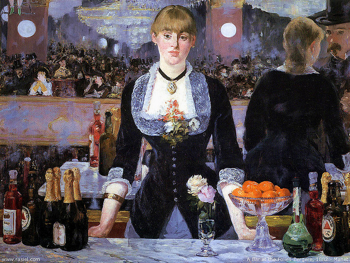

It was saying No to the strange idea of the life I imagined then, as something that could be lived silently – standing like the figure of the bartender in the great Manet painting of the Folies Bergeres – the woman who stares, whom you can’t take your eyes from, but who is herself only a created image – a great one, to be sure – not a person at all.

I could see the end of playing roles as a choice that said “Yes” to trying to put together a life of my creating, of my battling, of my acceptance of myself. It said “No” to the constant retreat into fictional characters so that I could feel the high of those sparking moments when the audience was mine.

It was an attempt to stop being driven by fear and the inner conviction of worthlessness, and to take on the struggle of living in spite of the fear. That sounds too heroic, but I emphasize that I’m looking far into the past to reinterpret the way I see my life with depression. At the time, I felt the fear and shame more than anything. Only now can I give myself credit for a resilience I took for granted all those years ago.

Since then I’ve done many types of work, and each one demanded that I play a role before an audience of some kind. A teacher facing students, a manager reporting to a board of directors, a consultant providing services to clients, an entrepreneur persuading investors, a mediator working with an angry group, a writer listening to readers.

I’ve pushed myself into some of those roles for the same reason I tried acting, to find a way to fill the emptiness inside, to make up for a core of human worth my depressed mind imagined was missing. That never worked. Others fit me well because I knew first who I was and used those roles to express something I had to offer – though it has never been easy to be comfortable in my own skin.

I am always having to fight the temptation to take the approval or rejection of the audience I’m facing as a sign of what I am worth as a human being.

What is the balance you find in the midst of depression between the role you play and your sense of who you are? Can you stand on your own apart from that work role, or do you need to be immersed in the work to feel like a valuable human being? That’s still a hard one for me.

I was just thinking, while reading this, about how differently you handled shame and feelings of worthlessness from what I did. I wouldn’t have even tried acting because I KNEW I couldn’t do it well enough – ever. I should say, I did try it briefly and felt like I could never get out of myself enough to become another character. Even now, performing in a show choir, the little bit of “acting” that I have to do along with the singing has been a painful process. This is my third year and it’s finally getting to be a little easier as I listen less and less to the criticism in my head. I still won’t watch any videos I’m in, though – just can’t do it because then I am in a position where I can be brutally critical of myself. Why I do it, though, is for the love of music, where I don’t feel any judgment and I’d do it even if there were never an audience.

I have to admit that, as a young adult, I abused alcohol to tolerate social situations and feel like I was somebody – who, exactly, I don’t know, but at least I could fit in with the group if I could laugh, act funny and say exactly what I thought. I’m lucky I don’t have addiction problems (except for cigarettes, which habit I finally kicked 19 years ago), because that period of time could have easily led me down that path.

One of my problems at work was that I feared criticism so much that it kept me from being as creative as I might have otherwise been. I had a hard time playing roles that made me feel exposed. I never wanted to supervise anybody because I couldn’t tolerate conflict. If I’d had to fire someone, I probably would have wanted to shoot myself first! During the last decade of my career, I was forced to start acting like somebody I wasn’t just to keep my job. I had one boss, in particular, who always found me wanting and even though I knew she was half crazy, my fear was so great that I was always eding up believing she was right and myself woefully lacking. Being free of that now is an indescribable relief! At least now I only have my own critical voice to listen to! And it’s not as strong as it used to be. But I do wonder if I would again cave, given the right circumstances. I hope I don’t have to find out, yet it would be nice to know if I could be stronger now. I’ve noticed that as I get older, I’m developing more of a “Don’t mess with me!” attitude – not in a mean way, but in a way that feels like I don’t want to put up with a whole lot of other people’s stuff any more.

Hi, Judy –

I like especially what you say at the end – the Don’t mess with me attitude. That’s a great strength, to feel inwardly strong enough to fight off what someone else might say. I still have the tendency at first to crumble in self-doubt under an attack – to feel Oh, they can see what a jerk I am underneath the facade – but fortunately I’ve come a long way in restoring confidence in myself.

Keep on singing, forget the videos! John

Another poignant essay by John! It amazes me how deep you go and how much detail you put into your descriptions and reflections. Sometimes I think I would rather avoid that much pain and so do not want to look so deeply into all the negative thoughts I have. I would rather just sweep them under the rug, wishing them to disappear. You demonstrate courage by speaking it all out loud!

Anyways, I can totally identify with the acting thing but not in the way you mention. When I hit a really low day or two or more I will often say ‘that most of the time life is only good for me if I act as if it was good. If I can’t act, it is not good.’ Not sure if that makes any sense.

I don’t think I am looking for approval of any kind. But at some level I am probably convinced that I should only be with people if I am cheery….

Thanks, Wendy –

– Only be with people if I am cheery – That’s quite a burden you put on yourself. It reminds me of my own habit of not wanting to learn anything new in a class because I only want people to see that I’m already good at it. How’s that for ill-logic? Acting a role can be fulfilling, but whether you’re good or bad at the part, it’s terribly stressful to feel that you have to fit into one as a condition of being with people.

All my best to you — John

Dear John,

It’s interesting that you turned to a novel to illustrate your thinking. I think that both the past and the present are needed, because we each have a lifetime narrative, and the past sets a context for the present. In a way we are playing ourselves in the story. There is an Italian psychotherapist named Antonino Ferro who views psychotherapy as a means of telling a coherent story of a life, so perhaps that gives us an opportunity to see the character we wittingly, and unwittingly present.

If you will forgive the introduction of the deeply unfashionable Freud, he believed that the sign of a return of health in his patients was that they could love AND work again, in part because it was a meaningful way to make use of our weaknesses and strengths. They are the large roles of a person functioning usefully in society. But if we hide behind them (often behind the work, as an excuse not to deal with the love), then they become more dangerous. But we need personal roles in some way, too. We would not send a friendly child into the streets without also saying be careful, and we need to care for ourselves in the same way.

In a book called “The Weariness of the Self”, by Alain Ehrenberg a French sociologist looks at the history of depression in society, and reflects that in the latter half of the 20th Century, it may be that we have burdened the self with so much power – “You can be anything you choose if you only try hard enough” – that eventually the individual despairs. I wonder if we try so hard to be a “self” that is someone else’s ideal, and we experiment with so many versions that we lose track, and become weary.

Your Acceptance and Commitment approach perhaps offers you a chance to settle into the self that is your own, and I would suggest that that is a chapter in an ongoing narrative that included all those other experiments.

.

Hi, Anne –

Thank you for these thoughtful insights – beautifully put. I’m interested in the way narrative can be helpful with depression. In fact, there’s a Narrative Therapy – no surprise, since there are therapies based on almost everything these days. Story is powerful and pervasive in the way so many people think. I’ll get the Ehrenberg book. It reminds me of how deeply the hero myth is built into the stories we tell ourselves, especially about careers – succeeding, conquering the world, rising to the top – or, less bombastically, making a difference, changing things in a small way, making a contribution to society. If we can’t exert power in the world, we’ve failed the test and run ourselves down in the process.

John

After studying this for a very long time, I have been able to reduce the entire cognitive element to one simple but very transformational sentence.

“PAIN IS IN THE BODY BUT SUFFERING IS IN THE COMPARATIVE”

The rest of the issue I believe is complex wellness biochemistry. Hope this helps.

Hi, Daniel –

That’s a masterful way of compressing a lot of ideas. Even pain, though, is a set of signals from neurons that go back to the brain to be interpreted as hurt and suffering. The mind can also scream pain when there is no physical cause. Some people have learned to control the mind’s interpretation of pain signals through biofeedback and hypnosis. I have a post about Reynolds Price that goes into that. I take it you mean by “the comparative” the habit of comparing oneself to others – definitely the cause of untold suffering and anguish. I guess you’re also thinking of comparing what you’re feeling now with a way you used to feel in the past or prefer to feel at this moment – or in the future? Totally agree.

Thanks for your insights.

John

Thank you, for the website, and for “unpacking” the above, for others.

As Viktor Frankl made so clear in his writings, physical pain in the course of meaningful pursuit feels like meaningful sacrifice. It is much more bearable, mentally. Depression, to whatever extent it is cognitive and NOT simply low levels of neurotransmitters, involves SOME element of comparing the present moment to some other, in some way, and finding it lacking in some way. If we can avoid doing that…