My ongoing search for movies about depression is turning up a long list of great dramas. Here are seven more of my favorites.

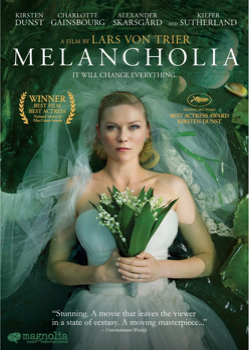

This extraordinarily beautiful film is the relentless portrayal of a depressed woman set against a background of the approaching end of the world. After alienating most of those close to her, Justine (Kirsten Dunst) relies on the support of her sister (Charlotte Gainsbourg), whose surface calm covers her own deep anxiety. In sharp contrast to the dulling impact of depression, the ultimate crisis facing humanity pushes most of the characters to the breaking point.

Kirsten Dunst’s performance is both powerful and agonizing to watch. In the first half, she walks in a daze through the motions of her elaborate wedding at the eerily perfect estate of her vastly wealthy family. The scenes have a painterly quality, accompanied by the haunting music of Wagner’s opera, Tristan and Isolde. In the second half, she falls into a near catatonic depression in which she can hardly dress, bathe or get into a car. As she recovers into a state of half-feeling, a functional anhedonia, she faces the coming destruction of the earth with greater calm than the rest of her family. Despite the fantasy-realism of the setting, the film shows the full range of depressive states with unflinching honesty.

Alfred Hitchcock’s famous films are his suspenseful thrillers, but The Wrong Man, from 1958, is completely different. In a black-and-white near documentary style, the film records the mistaken conviction of a jazz musician (Henry Fonda) for a robbery committed by a man who resembles him closely. Although the real criminal is eventually found and the “wrong man” released from prison, his years as a convict have a devastating effect on his family. His wife (Vera Miles) slips into a major depression and requires hospitalization. The portrayal of her slow decline is bleakly realistic. It’s a powerful, though neglected film.

The film adaptation of Susanna Kaysen’s memoir is set in the 1960s when psychiatric diagnosis was a lot different from what it is now. After attempting suicide, Susanna (Winona Ryder) is sent to McLean’s Hospital in the Boston suburbs with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. At the heart of her experience, however, is something much more like depression. Lost, empty, looking for a home, she convinces herself she’s found one among the fellow residents of her ward. She goes out of her way to fight the staff and dig herself deeper into isolation.

At her lowest point, she admits to the psychiatric nurse (Whoopee Goldberg) that she feels empty and wants to die. It’s her deep depression telling its truth, dropping the disguise of angry defiance. Since she hasn’t talked honestly to the psychiatrists about her feelings, the nurse urges her to write down exactly what she has told her. Susanna begins to keep a journal, and writing becomes the starting point of her recovery. It helps her find a purpose, explore the feelings she has kept hidden and ultimately get back to life outside the hospital.

Kevin Spacey plays a psychologist known as the “shrink to the stars” of Hollywood. He has written a best-selling book on happiness, but the film is about his deep depression following the suicide of his wife. He is full of anger and denial, unkempt and sleepless, bitter about life in general. During a TV interview, he tears up his happiness book, declares it a fraud and stalks off the set. His friends organize an intervention so that he will get help, but he attacks them furiously. Only a fine actor can render a self-absorbed, angry depression in a dramatically interesting way, and Spacey’s performance makes the film an absorbing experience.

Jane Campion directed this adaptation of Janet Frame’s autobiography. It dramatizes the New Zealand novelist’s story about her childhood, her eight years in a mental hospital and her early career as an award-winning writer. Although she was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the 1940s and almost lobotomized, it’s now thought that Janet Frame was not schizophrenic. The film presents the portrait of a young woman who seems to be depressed, socially anxious and too “strange” for her contemporaries to accept as normal. She accepts hospitalization and becomes comfortable with its hidden and undemanding life, even as she writes – and publishes – her first short stories.

She is finally discharged, just before her scheduled lobotomy, only because she has received a prestigious literary award. The film dramatizes the way she makes a new life for herself despite the stigma of mental illness and the difficulty she has in managing the basics of human relationships.

The suicides of five teenage sisters, with four of them taking their lives on the same evening, are a tragic mystery that no one can explain. The depiction of their lives in this film reveals a terrifying emptiness of feeling in each of them. It’s the bleakest form of depression I can imagine. They live with an almost comically restrictive mother – who wants to sterilize their existence of any hint of maturity – and a completely remote and ineffectual father. The parents regularly confine the girls in the house for any infraction of their rules.

Even though they resist close relationships with boys, they reach out to them by phone, written messages and rooftop meetings. Their intention seems purely manipulative. For the evening of their group suicide, the four girls lure a group of infatuated boys to meet up with them when their parents are away. Of course, they find horror instead of sex. The story is told from the point of view of those boys, and their infatuation and innocence emphasizes all the more how baffling the suicides are.

Woody Allen played the same wittily depressed character in all of his early films, but Interiors was his first decidedly unfunny drama and the first film he didn’t star in. It’s all about depression. Early in the film, an already depressed woman (Geraldine Page), a once successful interior decorator, hits bottom when her husband announces he wants to leave. This crisis strains the difficult relationships she has with her two grown daughters (Diane Keaton and Kristin Griffith), who also suffer from the depression they’ve grown up with.

It’s a convincing portrayal of the difficulties depression brings into all the relationships in the film – among the mother, daughters and their husbands. As the mother becomes more suicidal, the daughters struggle to deal with their own lives. They are all aware of depression as a problem but also seem blind to its deeper impacts on the entire family.

…..

Have you seen many of these movies? What have your reactions been? Please let me know if there are other films you would like to add to the list.

Hi John

Just curious, does watching these depressing movies pull your moods down again? I get very sad and remember my darkest days and it’s so hard for me to get out of the mood. I also end up having night mares

So I’ve been avoiding books and movies abotu depression for a while…

Noch Noch

Hi, Noch Noch –

I know what you mean – I used to avoid listening to music linked to depressive periods in my life. It’s different now – I’m not so fearful about depression or feeling fragile about recovery. So I don’t find well-made movies or books about depression to be depressing. That’s also because a good film dramatizes some process of change, and that is hopeful. Also a good film is a creative effort – like a Bob Dylan song about the end of the world or the bluest of jazz blues by a Miles Davis or John Coltrane. There’s an energy of life and hope in creating these things – so the dark feelings are moving, often painful to watch/ listen to, but don’t leave me feeling worse.

John