It took me a long time to understand the connection between depression and anger. One psychiatrist I visited would often ask a simple question toward the end of a session: How’s your anger?

I couldn’t understand why he asked. I hadn’t been talking about anger. Depression was my problem.

I’d usually respond with a puzzled, Fine. I’d leave his office wondering why he had asked about anger but soon put it out of my mind.

He never pressed me to talk about it, and I never asked for an explanation. After a while, though, I put the two together, and found a new way of looking at myself that went deeper than I had gone when focused only on depression.

I knew that irritability was on the list of depressive symptoms used for making a diagnosis. But I separated that in my mind from raw, hot-blooded anger.

Before saying any more, I want to distinguish between ordinary anger and the intense anger that leads to rage. Anger is a basic human emotion that helps defend us from attack. I think of it like pain – a powerful signal that demands a reaction.

You’re being accused unjustly. You’re being verbally or physically abused. You witness an act that violates basic norms of justice and humanity. You get angry, outraged at an attack on your integrity, your body, your loved ones. Anger alerts you to the need to react in order to defend your safety, family, identity, ideals – everything that makes you who you are.

That sort of anger is justified. Feeling and expressing it are inwardly satisfying because you’re standing up for yourself. If you were to stifle it, you’d probably feel ashamed that you let yourself be run over.

The anger that quickly leaps to rage is completely different. It may be triggered by an external provocation, but its causes are usually buried inside you. It’s more of a projection onto the world, a response that is far out of proportion to any cause.

Perhaps the hallmark of this sort of anger, like the intense forms of irritability, fear or despair, is that they perpetuate themselves. After a while, they simply take over. You’re raging, irritable, intensely anxious or despairing for no apparent reason. Or if there is a reason at the beginning, the distorted emotions keep going without letup. They have a life of their own.

Far from being satisfied at the expression of an understandable emotional reaction, I’d feel terrible and full of guilt. I’d try to apologize, but the damage was done.

There had been periods in my life when I had stormed and raged with my unfortunate family for no apparent reason – though at the time I found plenty of things to yell about.

Those “causes” were usually small stuff. The house is a mess – meaning all I could see was a disorder I couldn’t stand, viscerally couldn’t tolerate. The kids had to be controlled better. They were too wild. They were acting too much like … kids!

Sometimes, and I hate to think back on it, I got violent, threw things around, hit my sons. Mostly I mistreated them by yelling down whatever they tried to say. I raged for total obedience. I raged at my wife about anything that rubbed me the wrong way.

It never occurred to me that extreme anger might be related to depression. It amazes me now that I never made a connection. It amazes me even more that I never sought help to deal with the rage – whether or not it was linked to anything else.

Once it started, I couldn’t stop it, no matter how much I tried. I knew the triggers that could set me off as soon as I walked into the house – and it was at home where I raged most often. I could anticipate the problems and knew how crazy it was to start yelling about stupid little things. I couldn’t stand what I was doing. But I couldn’t stop feeling the rage.

Then I read Terrence Real’s I Don’t Want to Talk About It, and everything started to fall into place. Real’s book is about depressed men, in particular, and is based on his long experience with couples and family therapy.

During many an intense session, wall-punching anger rushed out of men who found it impossible to talk about their feelings. Real came to think of this as a covert form of depression because sooner or later a full-blown depressive episode would set in.

Using the anger to probe its origin, he usually found a deep shame that had developed early in life. There was a sense of failure to achieve the ideals of manhood that his client had been expected to meet. Traumatic events had pushed the boy over the brink and led to his sealing emotions away so deeply that he lost touch with them altogether.

Whether or not you agree with this type of explanation, the drama that unfolded in his office brought out a deep connection between the extremes of anger and depression.

I had lived through moments exactly like the scenes Real’s clients described and often acted out in his presence.

Whatever the explanation, I finally felt the relationship between depression and extreme anger. I had been swinging from one mood to another, a period of explosive anger followed by a period of deep depression. From intense but destructive energy to no energy at all.

As I had found so many times, awareness was the first step in healing. I couldn’t stop either the anger or the depression on my own but could see what they were doing to me. That prompted me to get help and start a long process of recovery.

For the first time, I understood the psychiatrist’s question, and my raging anger became part of the discussion from then on.

In a later post, I’ll talk about how I’ve been able to limit and manage this dimension of depression.

Is this form of anger part of your experience of depression?

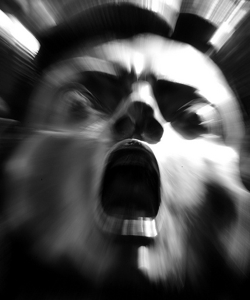

Image by RTP (Really Terrible Photographer) at Flickr