The more I get into the research on antidepressants, the more questions I have. In the last post, I raised issues about the endless search for the right medication; the discouraging record of relapse after becoming symptom-free; and the puzzling primacy of antidepressant treatment for an illness with complex causes that go way beyond biology.

Those questions are only the starters. I have even greater concern about long-term antidepressant treatment. Most psychiatrists consider it necessary for severe, recurrent illness, but others – apparently a small minority – are speaking out about adverse effects of using these drugs for prolonged periods.

My experience with long-term treatment has made me skeptical of the value of antidepressants, but recent studies make me worry that I might have been harmed as well. So I’m looking for an answer to a question that I’d rather not have to ask at all.

Can long-term antidepressant use worsen depression?

Many Antidepressants, Little Relief

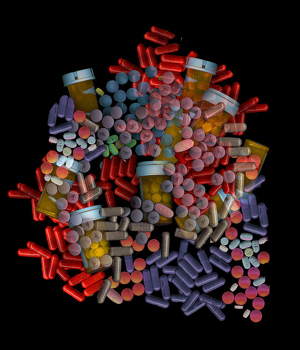

For years, I was convinced of the necessity of taking these drugs. I had no hesitation about taking multiple meds for depression, anxiety, poor concentration and sleep problems – 20 different drugs over the last 16 years.

Over time, it became clear that antidepressants weren’t doing much for me. Nevertheless, I kept thinking that I’d be in worse shape if I stopped. In other words, I was driven by fear. So I kept on going and wound up taking at least one sample of each class of antidepressants:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (RI) (Zoloft, Paxil, Celexa, Lexapro, Luvox)

- Serotonin Norepinephine RI (Effexor, Cymbalta)

- Norepinephrine Dopamine RI (Wellbutrin)

- Norepinephrine RI (Strattera)

- Tricyclic (Imipramine)

- Atypical (Trazodone)

I took some of these alone but more often in combinations. I also used other drugs to help with mental energy and concentration, anxiety and insomnia.

The guiding assumption of all the psychiatrists who treated me was that failure of one medication should be followed by others until an effective one was found. No psychiatrist ever suggested that I should stop using antidepressants. They assumed that stopping treatment would lead to relapse. (It didn’t seem to matter that I had not recovered enough to qualify for relapse.)

Depression gets worse, then better – for a while.

During this long period, the recurring major depressive episodes became more and more severe, but that wasn’t the worst of it. Episodes come and go, but I also noticed a gradual deterioration of short-term memory and the ability to concentrate. Anxiety in groups skyrocketed, and I also had frequent periods of feeling dissociated from everything around me. These were the problems that eventually made it impossible to my professional work.

However, I did improve a great deal with my 12th antidepressant. This was an MAOI (monoamine oxidase inhibitor), a class of antidepressants regarded now as a last resort because it requires dietary restrictions. Twelve years of misery with major depression is a poor tradeoff for a few items in my diet, but that’s the way it worked out.

The MAOI I’m using is Emsam, or selegiline taken through a 24-hour patch. This wasn’t the final word, however. It failed after a great year and a half and was then supplemented with lamotrigine, a mood stabilizer used to treat bipolar illness. (Before lamotrigine, I tried lithium, another mood stabilizer, but that made me feel as if all my brain circuits had been disconnected.)

The addition of lamotrigine to Emsam restored me again, this time for about two years. I intend to withdraw from these drugs over a very long period of time since they don’t seem to be doing much now. But there won’t be any more medications after this. I’ve found other types of treatment to keep myself healthy.

What was the effect of all these drugs?

The accepted wisdom is that I should stay with antidepressants because there’s a strong likelihood that I’ll head into another major depressive episode soon after I stop. I have to say that my highly unscientific reaction to that idea is – No-duh.

After all, my brain’s neurotransmitter systems have been getting used to living on various drugs for 16 years. They must have made some adaptation by now to this steady, artificial diet. So, sure, there will be a reaction after you stop pumping drugs in there.

Is there any evidence that the brain really does adapt in this way?

That question leads to a much greater concern. Why have the symptoms of depression progressively worsened over time, despite constant medication? Is it possible that the drugs designed to prevent relapse have done more long-term harm than good? Would I have been better off if I had never taken antidepressants at all?

Of course, I’ll never know for sure what might have been, but I have found studies that answer “maybe” to these disturbing questions.

Can long-term antidepressant treatment cause harm?

Giovanni Fava has been posing the question of potential long-term changes in brain function caused by antidepressants since the early 1990’s. In a 2010 paper, he says that antidepressants are crucial for the treatment of depressive episodes in the acute phase when untreated symptoms are at their worst. With long-term use, however, the brain sets to work compensating for the drug-induced changes with a process he calls oppositional tolerance.

The brain tries to re-establish its usual balance of production, release and reuptake of neurotransmitters – as every system of the body does when its normal functioning has been disturbed. The idea is that if the medication artificially jacks up the brain’s level of serotonin or norepinephrine, the neurobiology of the system reacts by reducing its own production of the neurotransmitter. In other words, if antidepressant use continues long enough, the brain will create a system to cancel out its effect.

A paper published this year adds to Fava’s findings the new idea of tardive dysphoria, a slow-onset depression induced by long-term medication use. The lead researcher, Rif El Mallakh, points out that resistance to treatment with antidepressants has dramatically increased, from 10-15% of patients in the early 90s to 40% in 2006. This corresponds to the period of explosive growth in the use of these drugs, especially for long-term maintenance treatment designed to protect against relapse.

There are many possible reasons for this huge change, but he focuses on the possibility that antidepressant use itself could be causing the problem. He discusses specific neurobiological reactions that could account for the emergence of higher levels of resistance to treatment. In addition, he cites evidence that stopping antidepressants in people who no longer respond to them can lead to reversal of symptoms as the brain compensates once more, this time for the withdrawal of the drugs. For some people, however, stopping the medication has no effect. They continue to have recurring depression. If antidepressant treatment is restored as a response, these patients can develop a permanently recurring illness. This is tardive dysphoria.

Could this explain my history with antidepressants? It’s a little late to freak out, but … !

Mainstream practice: stay with antidepressants

The general attitude among psychiatrists is firmly on the side of long-term, even lifetime, use of antidepressants as the best protection against relapse. This is the recommended treatment for people with my condition – numerous recurrences of depression over many years, high frequency of recurrence and a family history of the illness. The rationale for this approach is that patients on extended drug use have less chance of relapse than those who go untreated.

I have trouble following the evidence and reasoning that leads to this treatment recommendation, but I’ll save that for another post.

You can read an interesting report on a roundtable discussion among 6 psychiatrists who strongly believe in long-term treatment with antidepressants. Their views are not monolithic and reveal a lot of debate within this community of practitioners. The paper is Preventing Recurrent Depression: Long-Term Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder.

I’d like to think that my experience with antidepressants, while it may have been pretty disappointing, didn’t worsen my condition. But now I’m finding that these drugs could have done a lot more harm than good.

I can’t change the past, but I hope my history with medications isn’t going to cloud my future.

Robert Whitaker has explored all these questions about treatment for depression and other mental illnesses in Anatomy of an Epidemic. He also has a good article on tardive dysphoria on his blog at Psychology Today.

Image by psyberartist at Flickr